Mamady Doumbouya, President of Guinea (since Oct 1, 2021)

Mamady Doumbouya (born 4 March 1980) is a Guinean military officer serving as the interim president of Guinea since 1 October 2021. Doumbouya led a coup d’état on 5 September 2021 that overthrew the previous president, Alpha Condé. He is a member of the Guinean Special Forces Group and a former French legionnaire. On the day of the coup, Doumbouya issued a broadcast on state television declaring that his faction had dissolved the government and constitution. On 1 October 2021, Doumbouya was sworn in as interim president.

Mamady Doumbouya (born 4 March 1980) is a Guinean military officer serving as the interim president of Guinea since 1 October 2021. Doumbouya led a coup d’état on 5 September 2021 that overthrew the previous president, Alpha Condé. He is a member of the Guinean Special Forces Group and a former French legionnaire. On the day of the coup, Doumbouya issued a broadcast on state television declaring that his faction had dissolved the government and constitution. On 1 October 2021, Doumbouya was sworn in as interim president.

Doumbouya was the instigator of the 5 September 2021 Guinean coup d’état, in which the president of Guinea, Alpha Condé, was detained. Doumbouya issued a broadcast on state television declaring that his faction had dissolved the government and constitution. He also said that the “National Committee of Reconciliation and Development (CNRD), [was forced] to take its responsibility” after “the dire political-situation of our country, the instrumentalization of the judiciary, the non-respect of democratic principles, the extreme politicization of public administration, as well as poverty and corruption.” In justifying the military’s actions, Doumbouya quoted the former Ghanaian president Jerry Rawlings, who said that “if the people are crushed by their elites, it is up to the army to give the people their freedom.”

Doumbouya is married to Lauriane Doumbouya, who is an active duty member of the French National Gendarmerie. The couple have three children.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mamady_Doumbouya

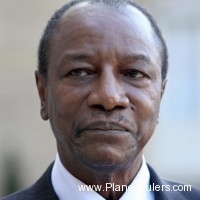

Alpha Conde, Former President of Guinea (since Dec 21, 2010)

UPDATE from Oct 11, 2015: In presidential elections, incumbent Alpha Conde wins 57.8% of the vote.

UPDATE from Oct 11, 2015: In presidential elections, incumbent Alpha Conde wins 57.8% of the vote.

Alpha Conde (born March 4, 1938) is the current President of Guinea (took office on 21 December 2010). Alpha Conde is the leader of the Rally of the People of Guinea (RPG), was candidate for the presidential election announced by the Ouagadougou agreements (signed January 15, 2010 by Camara and General Konate, under the auspices of Blaise Compaore, President of Burkina Faso) and the first round was held on June 27, 2010. Born in Boke (Lower Guinea), Alpha Conde left for France at the age of 15 years attend high school and university (Sciences Po Paris, Sorbonne). In 1970, he was a victim of the regime of President Sekou Toure, who condemned him to death in absentia. He is then forced, like many of his fellow intellectuals, to remain in exile from his country. Alpha Conde is in Conakry since May 17, 1991, when the end of his exile and his return to Guinea.

Presidential election of 1993

On his return to Guinea, Alpha Conde succeeds, along with other opposition leaders in Guinea (Bah Mamadou Bhoye, Siradiou Diallo, Jean-Marie Dore, Masour Kaba, etc.), to impose area multiparty system which allows the presence several opposition parties in Guinea. Then, he took part in the country’s first multiparty election in December 1993 after three decades of authoritarian rule. In the poll, Condé challengers of General Lansana Conte, president since the coup of 1984. General Conté was declared winner with 51.7% while domestic and international observers charged with overseeing the election denounced a strong climate of fraud and that the unanimous opposition contests the official results. Conde’s supporters protest particularly against the annulment by the Supreme Court of the full results for the prefectures of Siguiri and Kankan, where Alpha Conde was probably a strong majority. Conde asks his supporters not to take the risk to cause a civil war and concentrate their efforts on the next ballot.

1998 presidential election

Following presidential elections in December 1998, Alpha Conde ran again but he is kidnapped and imprisoned without trial by the end of the poll.

Official results released by the Government Lansana Conte declared winner of first round (56.1%) followed by Mamadou Boye Bâ (24.6%). On 16 December, two days after the election, many opposition leaders are arrested for allegedly preparing a rebellion against the dictatorship in place. The following months will be abuses committed by military forces on opposition supporters.

Imprisonment

Alpha Conde is kept in prison for more than 20 months before the government does a special court to try him. This incarceration without trial raises a strong international protest movement. Amnesty International alleges a violation of Human Rights and the Council of the Interparliamentary Union in violation of parliamentary immunity including Alpha Conde enjoys as a member of Guinea. Many voices throughout his imprisonment to request his immediate release. Including those of Albert Bourgi, organizing a major movement to support “the committee of Liberation” to Alpha Conde, and Tiken Jah Fakoly, author of “Free Alpha Conde” addressed to General Lansana Conte, and that youth turns into hymn to the glory of martyrs and political prisoners in Africa. Conde also receives support from foreign heads of diplomacy, like Madeleine Albright (U.S.) who moves well in Conakry. In France, President Jacques Chirac personally involved. Its mobilization reinforces the many requests from other heads of state formally requesting the quick release of Alpha Conde.

Conde was sentenced in 2000 to 5 years in prison for “undermining the authority of the State and the integrity of national territory” after a sensational trial in the discredited African and international press. He was finally released on 2001 and is the subject of a presidential pardon.

The Alpha Condé affair

“The Alpha Condé affair” as she is often portrayed in the press, referring to the Dreyfus affair in France in the nineteenth century, resulting in a sensational trial and marks a significant political turning point for Guinea. Alpha Conde, was released May 18, 2001, when it undergoes a presidential pardon, 28 months after his arrest and eight months after his trial organized by the “Court of State Security Guinea, which is specially constituted for this purpose. The trial of five months beginning April 12, 2000, after several postponements, the first condemned to five years’ imprisonment for “endangering the security of the State of Guinea” and “unlawful use of armed force” Monday, September 11, 2000. It becomes particularly among youth, a symbol compared to Mandela. Alpha Conde himself often cites Mandela as an example in these political considerations. He said his release “on the African political scene, one can speak of a before and an after Mandela. It is, henceforth, the reference and model for all those struggling for unity, reconciliation and peaceful advent of democracy …. ”

Coming to power of the military junta and 2010 presidential elections

Since the death of Lansana Conte in December 2008 and the seizure of power by the military junta Camara, Alpha Conde has focused policy on the return to civilian rule and fair elections, transparent and inclusive. He has done in the “Forces Vives formed the opposition, unions and other civil society actors. In an article published by Le Monde in January 2010, he declared that the massacres of September 28 in Conakry stadium highlight the need for a complete break with the past: “The trauma, once again, this day by the people, definitely discredits all those who, near or far, have their share of responsibility in these killings. The consequences of this tragedy ordered a mandatory break from all that has been considered previously. They must now encourage all actors in Guinea, with the support of external partners, to organize prompt elections, which will only legitimize the future leaders based on mechanisms other than those which led to the emergence of the system to abolish. . In February 2010 he announced in Conakry his party’s candidacy for the presidential elections of June 2010.

Academic background

After studying at the Sorbonne, Alpha Conde graduated Higher Studies (DES) before becoming a Ph.D. in public law at the Law Faculty of Paris, Pantheon. The professional career of Alpha Conde began as a teacher: he teaches courses in the Faculty of Law and Economics (Paris I, Panthéon Sorbonne) for over ten years and at the School of Post, Telephone, Telecommunications (PTT). Students Federation of Black Africa in France He fought alongside in the union of higher education (SNESUP) and combines the functions of Head in the Guinean Association of Students in France (AEGF) and within Federation of Students of Black Africa in France (FEANF) where he is, from 1967 to 1975, the Executive Coordinator of the African national groups (NG), which oversee the activities of the Directorate of FEANF. He is the president of the organization in 1963.

Publications

Alpha Conde participates in the newspaper “the Guinean students” before they write for other journals and academic books. He published a book entitled Political: “Guinea, Albania African American or neo-colony” (published by Git-le-heart, 1972). He goes through various publications, both booklets (“The future of Guinea, in May 1984,” Proposals for Guinea in December 1984, “For that hope dies” in August 1985, “Where are Us, “” Three years after, “and” The fish rots from the head “) as newspapers (” The Patriot “was established in January 1985 and banned three months later);” Segueti “and” Malania. With the accession of Guinea’s independence in 1958, schoolchildren and students is incorporated into Guinean Youth African Democratic Rally (JRDA). Alpha Conde, who was active in the Association of Guinean students in France (AEGF) adheres to that organization.

DND to RPG

In 1977, following the tripartite meeting in Monrovia of reconciliation between President Sekou Toure, Houphouet Boigny and Leopold Sedar Senghor, Alpha Conde created the National Democratic Movement (DND) with Prof. Alfa Ibrahima Sow, Bayo Khalifa and Other founding members. The MND will undergo several changes in the underground struggle to fight semi-clandestine and finally to the legal battle since 1991. The MND is the first UJP (Unity, Justice, Homeland) and RPG (Rally of the Guinean Patriots) to finally be the current RPG (Rally of the People of Guinea).

Rally of the People of Guinea (RPG)

The RPG is now one of the largest political groupings in the country. Present throughout the territory with a national office and 85 national sections, the RPG is a party strong presence.

Sékouba Konaté, Former Acting President of Guinea

Brigadier General Sékouba Konaté (born 1964) is an officer of the Guinean army and the Vice President of its military junta, the National Council for Democracy and Development. After attending military academy, he received the nickname “El Tigre” for his action in battle, and gained such popularity with the people he was favored to be president of the government. However, he was appointed Vice-President; but took control of the country when the president was shot in December 2009.

Konaté was born in Conakry in 1964 to Mandinka parents. He attended the Académie Militaire Royale in the Moroccan city of Meknes, graduating in 1990. He suffers from an unknown physical illness, possibly of his liver.

For his military prowess in combat, Konaté was nicknamed “El Tigre”. He was trained as a parachutist, and fought in many battles in Guinea’s military during 2000-2001. Because of his reputation as a soldier, many people supported him to be the junta leader: he is still popular with the people.

Guinea’s President, Lansana Conté, died after a long illness in December 2008. The day afterwards, Moussa Camara, a military captain, stepped forward and declared Guinea to be under junta rule, with himself as the head. Konaté demanded that he be considered to rule the junta, and Camara and him drew lots to determine who would be President. After drawing twice, due to accusations of Camara cheating, Konaté was made the Vice President. He was also made the Minister of Defense.

On December 3, 2009, Camara was shot in an attempted assassination by his aide-de-camp, Aboubacar Diakité. While he was airlifted to Morocco for treatment, Konaté was placed in charge of the country. With Camara still in rehabilitation, the United States government has expressed its desire to see Camara kept out of Guinea and Konaté placed as head of the junta, because: “All of Camara’s actions were ill concealed attempts to take over… we’re not getting that same sense from Konate,” according to the United States Deputy Secretary of State William Fitzgerald.

Lansana Conté, Former President of Guinea (up until Dec 2008)

Personal Information

Born c. 1944 in a village about 50 miles north of Conakry, Guinea. Member of the Soussou ethnic group.

Career

President of Guinea, 1984–; assumed leadership in a military coup following the death of President Sekou Toure; founder of Military Committee of Recovery (CMRN), 1984 (dissolved, 1991); founder of Transitional Committee for National Recovery (CTRN), 1991; candidate of the Party for Unity and Progress (PUP) in first multiparty presidential elections; won election, 1993. Promoted from colonel to brigadier-general following successful defense against a coup attempt in 1985.

Life’s Work

General Lansana Conte has led the West African nation of Guinea on a slow path toward democratization since assuming power during a military coup in 1984. His political and economic policies–based on the free market system–have made Guinea more attractive to foreign investors despite lingering economic austerity in the mineral-rich nation. Slow and deliberate in leadership style, Cont, takes his time making important policy decisions–a tendency that has led opposition groups to demonstrate for a more rapid introduction of democratic reforms.

Conte is a military leader who also enjoys the support of much of the populace, having for the most part avoided the harsh dictatorial style of his predecessor, Sekou Toure. He has taken pains to maintain an ethnic balance within his government and has thus avoided the ethnic violence endemic to some other African nations. On the other hand, Conte has frequently reshuffled his cabinet, called the Council of Ministers, to remove potential adversaries from the center of political power.

His popularity, which reached a peak during an aborted coup attempt in 1985, eroded amidst continued persecution of opposition groups and delays in the implementation of presidential elections. Some observers have charged that the former professional soldier remains a one-man ruler in Guinea.

Throughout his first ten years as president, Conte has enjoyed the support of the military, whom he has protected to some extent from his economic reforms. Support also comes from the French, with whom he has established improved relations. Other nations as well have been attracted by his openness to the West and his attempts at democratization, and major foreign lenders like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have rewarded his economic reforms by granting additional loans.

Guinea is potentially one of Africa’s richest nations, due to its mineral resources such as bauxite (used in the production of aluminum), iron ore, and diamonds. In addition to its minerals, the country’s agricultural and industrial sectors offer the promise of further development. Still Guinea remains a poor country with a host of economic problems. Its weaknesses include a lack of highly trained managers and an underdeveloped infrastructure of transportation and communications.

Guinea achieved its independence from France in 1958. It was ruled by Sekou Toure, its first president, from 1958 until his death in 1984. Toure was a harsh dictator who left the country in economic chaos after 25 years of economic mismanagement under a socialist regime. He was also a highly suspicious leader who used the police powers of the state to terrorize and subdue his opponents as well as the general population.

Sekou Toure died unexpectedly on March 26, 1984, during heart surgery in Cleveland, Ohio. There was no clearly established successor to the Guinean president, so within two weeks the army stepped in and took over the government. The bloodless coup was led by two colonels, Lansana Conte and Diarra Traore. Conte became president, and Traore became prime minister. Toure’s political party, the Guinean Democratic Party (PDG), was abolished, and the new government established the Military Committee of National Recovery (CMRN) as the country’s ruling body. No other political parties were recognized at the time.

The new military leaders were greeted enthusiastically by the citizens of Guinea, and especially by the country’s youth. For them, the 1984 coup marked an end to Toure’s reign of political and economic control. Among the promises made by the new military leaders was a new era of freedom. The violence and disastrous economic policies of the prior regime were denounced, and Conte promised there would be no executions. Some former leaders of Toure’s party were jailed, while other political prisoners were freed. At least at first, the Conte government was perceived as open and magnanimous, not only to the populace of Guinea but also to Western nations long shunned by Toure.

Conte and the CMRN were faced with the task of political and economic reform, some of which had been started in the last year’s of Toure’s regime. Toure’s rule as president was one of ethnic domination by his own Malinke people. Conte, a member of the Soussou ethnic group, sought to ease tensions by creating a pluralist government in which all ethnic groups would be represented. On the economic front, he needed to make the country more attractive to foreign investors.

Following years of corruption under Toure, the government bureaucracy, civil service, and state-run organizations were badly in need of reform. Unfortunately, the ruling body created by the military proved to be too diverse, with no clear political direction. Disagreements arose concerning which economic changes were possible or even necessary.

Within months of the coup, a power struggle developed between President Conte and Prime Minister Traore. Like Toure, Traore was a Malinke, and he was seen to favor his own people as the government was being reorganized. Africa Record described Traore as “impetuous and self-serving.” Clearly ambitious, he tried to rally support for himself within Guinea as well as abroad. He took a higher profile than Conte, making state visits to Paris and London, and single-handedly authorized major expenditures without anyone else’s approval or consent.

In December of 1984 Conte abolished the position of prime minister and demoted Traore to minister of state for national education, one of four newly-created state minister posts. Traore refused to acknowledge changes in the balance of power and continued to occupy the prime minister’s residence. Animosity between the two leaders continued into 1985.

In January of 1985 the death of Captain Mamady Mansare, a close friend of Traore’s, was announced. No announcement was made, however, of an attempted coup against the Conte government that resulted in the arrest of 41 soldiers. The suppression of a more serious coup attempt came in July of 1985, when Colonel Traore spearheaded a takeover attempt while Conte was out of the country attending a regional summit meeting in Togo. Traore’s forces succeeded in capturing a radio station in the Guinean capital of Conakry, and Traore went on the air to announce the dissolution of the CMRN and formation of a new government. However, soldiers loyal to Conte quickly regained control, and Conte returned to the capital two days later. Traore and his family were arrested as part of a purge of coup sympathizers, both military and civilian. Colonel Traore was executed almost immediately, and no public trials were ever held for the estimated 200 people arrested for allegedly taking part in the coup attempt. The plot was described as an attempt to reassert Malinke rule and return to the authoritarian practices of Sekou Toure, although Conte and the CMRN tried to downplay the ethnic aspect of the failed attempt in order to minimize ethnic tensions.

Conte was promoted to brigadier-general after successfully defeating the coup attempt. It seemed as if the entire incident only served to strengthen his position in the government and improve his public image. He was able to consolidate his personal power, although he would continue to face opposition from different segments of Guinean society throughout the years to come.

Following the failed coup attempt in July of 1985, Conte took his time and spent the remainder of the year deciding on a new government and initiating new economic reforms. According to Africa Report, the reason for the delay was Conte’s desire to “deliberate carefully before coming to an important decision.” Although the delay in forming a new government gave the impression of indecision and weakness, Conte was able to remain firmly in control and form a new government to boost the nation’s confidence in his leadership.

When Conte announced the new Council of Ministers in December of 1985, he increased the number of civilian ministers from nine to 19 and reduced the number of military ministers to 12, thus giving civilians a majority over the military for the first time. He also diminished the influence of potential military rivals by sending them to remote parts of Guinea as resident ministers, an action he would take again in the future.

Another notable characteristic of the new government was a bigger role given to expatriate Guineans, some of whom returned from long exile to accept cabinet positions. This step was intended to attract investment from wealthy Guinean traders who had left the country under Sekou Toure’s rule. Technocrats were appointed to other cabinet positions, helping to give the cabinet the appearance of being ready to deal with economic reform.

Conte strengthened his personal power by appointing a key supporter, Commander Kerfalla Camara, as permanent secretary of the CMRN. By appointing minister-delegates to other sensitive cabinet positions, Conte became personally responsible for the key portfolios of defense, information, planning and international cooperation, and interior and centralization. He also reorganized the armed forces command and placed close associates in charge of key posts.

Following the 1985 reorganization, the first steps toward democratization were taken by allowing district council elections in Conakry in April of 1986. A plan developed with the help of French advisors called for introducing such local councils throughout the country.

Although Conte and the CMRN had clear intentions of liberalizing Guinean politics after taking power in 1984, no formal announcement of constitutional reform was made until Conte’s speech on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of Guinea’s independence. With Guinea’s constitution suspended since April of 1984, Conte announced in October of 1988 that a new constitution would be drawn up. He characterized the four and one-half years of CMRN rule as a “transitional period” that had reached its conclusion.

While citing continuing problems with official corruption and embezzlement, Conte announced the following year that Guinea would make the transition to a multiparty democracy during a five-year period that would follow the adoption of a new constitution. The constitution would be drafted by a commission of Guineans, and the CMRN would be replaced with a Transitional Committee for National Recovery (CTRN) to rule during the five-year transitional period.

While the 1989 plan set no definite date for adopting a new constitution, it proposed the CTRN have an equal number of military and civilian members. Only two official political parties would be allowed, there would be a unicameral National Assembly, and the president would be elected by popular vote for a five-year term and could be re-elected only once.

In 1990 the new constitution was drafted by a commission headed by Foreign Minister Major Jean Traore. At this time the government’s call for exiled opposition leaders to return to Guinea to participate in the political liberalization was largely ignored. Opposition groups in exile rejected the new constitution and called for a voter. They demanded an immediate end to military rule (rather than a five-year transitional period) and a national conference of all political groups. In August of 1990 three members of major opposition groups were arrested, and they later received prison sentences on charges of forging official documents and distributing banned newspapers.

On December 23, 1990, the new constitution was approved in a popular referendum. Some 97 percent of the electorate turned out, and 98.7 percent of those voting approved the new constitution. As announced the previous year, it called for the formation of a CTRN to replace the CMRN and the creation of a two-party democratic system within five years.

In January of 1991 the CMRN was dissolved and a 36-member CTRN was appointed. Under the new constitution, members of the CTRN could not hold cabinet positions. Later in the year Conte announced that legislation for the adoption of democracy would be ready by the end of 1991. He also announced that although a two-party system was expected, more parties might be allowed under certain conditions. Speeding up the process of democratization somewhat, Conte announced in October of 1991 that a full multiparty system would come into operation starting in April of 1992. Legislation passed at the end of 1991 made the CTRN’s job more or less complete, and as a result its size was cut from 36 to 15. Conte resigned as president of the CTRN early in 1992 in response to charges that the country’s executive and legislative branches should remain separated.

Conte continued to move Guinea toward full democratization when he announced in September of 1993 that the country’s first multiparty presidential elections would be held on December 5, 1993. As a candidate of the Party for Unity and Progress (PUP), he won the election with just over 50 percent of the vote. Legislative elections were scheduled for 60 days after the presidential poll.

Throughout his first ten years as president of Guinea, Conte enacted the necessary economic and political reforms that would provide for a better standard of living in Guinea. Although he has faced opposition–either because his economic reforms were too difficult or his political reforms moved too slowly–he has taken appropriate measures to meet the demands of his opponents or to deal with them in an appropriate political or military manner. His able rule had taken Guinea far along the path of liberal political and economic reform, steps necessary for a country that suffered for most of its first 25 years of independence under a harsh dictatorial ruler.