Career

President of Uganda, January 29, 1986–. Government research assistant, 1970-71; leader of resistance movements against dictators in Uganda, 1971-86, including Front for National Salvation, 1974-79, and National Resistance Army, 1980-86; entered capital city of Kampala by force in January 1986 with aid of majority of Ugandan citizenry. Founder and head of National Resistance Movement, Uganda’s only legal political organization.

Life’s Work

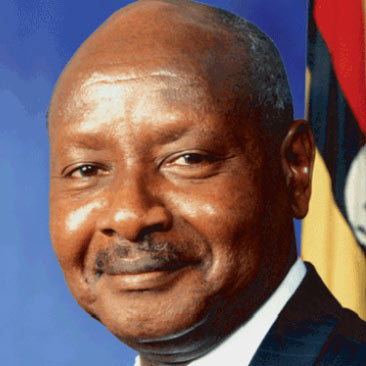

Yoweri Museveni, the president of Uganda, has faced the staggering task of restoring peace and prosperity to a nation devastated by fifteen years of civil war. Museveni assumed the presidency of Uganda on January 29, 1986, after troops under his leadership stormed the capital city of Kampala. Since then he has tried to reverse two decades of army brutalities, government corruption, and economic decline in Uganda, formerly one of Africa’s most prosperous countries. “I’ve got a mission,” he told Time magazine, “–to transform Uganda from a backward country to an advanced country.” In Africa Report he noted that his army “arrived here to find a bleeding nation. Insecurity was the order of the day. The moral fabric was in decay…. The crucial thing is to show [the Ugandan people] that there is a way out, that it is within our means to overcome this backwardness.”

Museveni’s National Resistance Army (NRA) has restored peace to most of Uganda. His National Resistance Movement–the only legal political organization in Uganda–has sought to reassure and unite a populace comprising some forty different ethnic groups. As Keith Richburg put it in the Washington Post, “Museveni dominates the government and has set the tone for the new Ugandan economic outlook. Yet he remains something of an enigma: a military man who came to power after leading a bush war but speaks more like a scholar with a firm grasp of international economics.” Richburg added that the president’s popularity “appears to lie in his ability to remind the outside world that, despite his government’s flaws, it is still far better than what preceded it.”

Uganda is a landlocked country in East Africa that is approximately the size of England. Although it has no coastline, it shares massive Lake Victoria with neighboring Kenya and Tanzania, and its rivers are plentiful. Once known as the “pearl of Africa,” its picturesque game reserves formed the backdrop for the filming of John Huston’s movie The African Queen. Unlike other African nations that suffer deadly droughts, rainfall and soil quality are good in Uganda, and crops are grown for consumption and export.

Atlantic contributor Robert D. Kaplan explained why the country has come to be known more for its bloody dictatorships than for its scenic waterways. “Uganda … whose arbitrary borders are the result of the 1884-1885 Berlin Conference of European powers, is so tribal that it is more like a loose association of many nations than like one,” wrote Kaplan. “It is as culturally diverse as India, as politically fragmented as Lebanon. A Western diplomat in Kampala says, ‘There are no horizontal linkages here–no unifying elements of history, ethnicity, or even religion. Nation-building can only start with particular groups and work upwards.'”

The British arrived in Uganda in 1862. At that time the country was a series of small nations, each with its own leadership, army, and ethnic identity. England granted Uganda “protectorate” status in 1894. Fewer white settlers moved in than in other areas of Africa, but Asia provided a mercantile class for the region during the first part of the twentieth century. Catholic and Protestant missionaries arrived and added more religious rivalries to an already tense ethnic situation.

Yoweri Museveni was born in a village in the Ankole province of southwestern Uganda. Even he is not sure exactly what year he was born, but most sources give the date as 1944. His father, a cattle rancher, was a proud veteran of World War II, having fought under the British flag in the King’s African Rifles brigade. Museveni’s family illustrates the complicated tribalism of the region. His father was a member of the Banyankole tribe, and his mother was a Banyarwanda, both subgroups of the Bantu peoples.

Museveni’s father insisted that all his children receive a thorough education. At the tender age of nine, Museveni was sent to boarding school, and he attended high school and took preparatory college classes at Ntare School in Mbarara, the district capital. He was a teenager when Britain granted Uganda its independence in 1962.

“It was a shattered polity that emerged at independence,” contended Kaplan. Under the protectorate, the British had promoted an Asian merchant class, a national army made up of minority tribes from northern Uganda, and a civil service run primarily by the Baganda peoples. The first prime minister, Milton Obote, came from a northern tribe, the Langi.

While Obote was struggling to control the various factions in Uganda, Yoweri Museveni emigrated to study political science and economics at University College in Dar es Salaam, the capital of Tanzania. Museveni obtained a bachelor’s degree in economics in 1970 and returned to his homeland to work in the Obote government. His tenure as a government official was short-lived, however. In January 1971 Obote was deposed by his top-ranking army officer, Idi Amin Dada. Immediately Amin launched a reign of terror that sent thousands of Ugandan academics, professionals, and businessmen into exile–and many thousands more to their graves.

As Kaplan explained: “Amin soaked this lush, sylvan country with the blood of several hundred thousand people. Several hundred thousand more were made homeless. The suffering was widespread, but not completely indiscriminate. All [northern tribesmen] were in danger. So was any Bantu with a house, a cat, or another possession that one of Amin’s thugs might covet.” Amin was the first dictator of Uganda to give his armed forces free reign over the citizenry. The country’s strong economy declined precipitously as crops and cattle were stolen, the mercantile class was expelled, and wanton torture and extortion prevailed.

Museveni took shelter in Tanzania, where he formed the Front for National Salvation (FRONASA), a group of exiles determined to oust Amin. He and his soldiers trained in Mozambique with a nationalist guerilla group and prepared to invade at the first sign of Amin’s weakness. In 1979, FRONASA united with a larger rebel band loyal to Obote, as well as Tanzanian forces, to drive Amin from Uganda. A hastily assembled coalition group known as the Uganda National Liberation Front took over Kampala in March of 1979. The entire country had been devastated by Amin and his army.

The task of rebuilding was enormous, and it was made even harder by the power struggle within Uganda’s coalition government. Museveni took the important job of defense minister in the Military Commission and was given the task of routing Amin’s army. Museveni used his FRONASA troops as well as other fighters recruited from his Banyankole tribe, and soon other government officials began to worry about the young commander’s growing strength. Museveni did not run the Military Commission, though–it was headed by a man loyal to Obote. Museveni watched with cynicism as the interim government called for national elections. These were held in December of 1980, and Obote, leader of the Uganda People’s Congress, won the presidency by a large margin.

Claiming that the election was rigged in Obote’s favor by his henchman on the Military Commission, Museveni returned to the bush with 26 followers on February 6, 1981. From that small cluster of supporters he forged the National Resistance Army–one of four rebel groups seeking to undermine the Obote regime. In Africa Report, Catharine Watson noted: “Museveni’s force grew slowly, based in Luwero, a fertile coffee-growing region just north of Kampala. Highly disciplined, its soldiers were mostly peasants from the south and the west, its commanders mostly from the west.” What made Museveni’s army unique was its respect for the citizenry. Museveni decreed harsh punishments for any NRA soldier found guilty of brutality or corruption. The tactic endeared him to the populace, and soon young orphans were flocking to his flag and embracing his vision of a better Uganda.

Kaplan has noted that Obote helped to undermine his own regime by resorting to the same tactics Amin had used. To quote Kaplan, the new government army quickly disintegrated into a rampaging mob. “The atrocities accelerated after 1980, and Obote made no visible attempt to stop them,” the observer claimed. “It seems that nothing was sacred to Obote’s soldiers. Skeletons exist of small children with their hands tied behind their backs. There are documented stories of gang rapes of girls as young as four. Torture, in which molten rubber was dripped onto a victim’s face from a burning tire suspended above, was administered by a paramilitary police unit…. Many Ugandans died from starvation; caught up in the turmoil, peasants frequently could not stay in one place long enough to harvest their usual crops.”

Museveni’s small army stood in stark contrast to this anarchy, and it gained power as the atrocities escalated. Obote’s regime fell in 1985 to a coup by army officers from a northern tribe. Still the government-sanctioned violence continued, especially against anyone perceived as a Museveni loyalist. Luwero, where the NRA was based, lost a third of its population in genocidal purges. Watson estimated in Africa Report that as many as 300,000 people died for supporting Yoweri Museveni.

Finally, in 1985, Museveni agreed to negotiate with the new military government of Tito Okello. Museveni refused to disband his army, however, and even as peace talks proceeded in Nairobi, Kenya, the atrocities continued in Uganda. A cease-fire was called by both sides, but it lasted only a few weeks. In January of 1986, Museveni mustered his forces–having grown considerably due to the government’s heavy-handed tactics–and marched on Kampala. Okello fled into exile, where he died in 1990. Museveni was sworn in as Uganda’s new president on January 29, 1986.

Dressed in army fatigues for his inauguration, Museveni declared, as printed in Time: “No one can think that what is happening today, what has been happening in the last few days, is a mere change of the guard. This is a fundamental change in the politics of our country.” The president emphasized that his administration would respect human rights and would not use a standing army as a tool for civilian intimidation. He promised to curtail government corruption and to try to restore Uganda’s failing economy.

At first Museveni attracted few believers elsewhere in the world, especially since his NRA troops continued to fight pitched battles against tribes in the northern sections of Uganda. Confidence grew steadily after 1986, largely because Museveni himself showed no signs of personal corruption, and because he promoted cabinet members from every ethnic group in the diverse nation. Signs of improvement were apparent. The Red Cross returned to Uganda after an absence of two decades. New trade agreements were initiated with the United States and other nations. The World Bank issued much-needed loans to buy equipment and repair roads and utilities. Museveni was elected president of the powerful Organization of African States. In a 1991 piece for Africa Report, Watson wrote: “On balance, the Uganda of today is leagues away from that of six, 10, or 20 years ago.”

Troubles remained, however. It was estimated that one million Ugandans were infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (commonly referred to as the HIV virus, which causes AIDS), even though Museveni was aggressive in his attempts to use state power to control the contagion. A great proportion of national expenditures still went to the military, and rebel activity continued sporadically among the northern tribes. Export profits rose after Museveni took control, but Uganda remained in the grip of an enormous debt incurred by the current president and his predecessors. Most importantly, the general movement toward multiparty democracy in Africa placed a burden on the Museveni regime because it was essentially a dictatorship. And Museveni was calling for a revised constitution.

Government corruption remained widespread in Uganda–and scattered human rights violations persisted–but wanton violence was no longer the norm. As Watson put it, “Security, both physical and psychological, has been restored.” Museveni brought Uganda back from a rule of terror and was presiding over the rebuilding process. A Kampala businessman commented in Time magazine: “Gone are the days when you had to hide your car from greedy soldiers and carry cash in your pockets to pay them off when they stopped you.”

In 1996 Musevini ran for president in Uganda’s first general elections since the suspect elections of 1980. He was opposed by two other candidates, including Paulo Ssemwogerere who had been a minister in the NRM government for 10 years. Museveni won the election with more than 75 percent of the vote, becoming the first directly elected president in the history of Uganda.

Museveni introduced measures to liberalize Uganda’s economy that included privatization, currency reform and a reworked agricultural market system. Although Uganda remains among the 10 poorest countries in the world, its economy has grown on average by more than 6.7% in the past 10 years. The country’s GDP doubled between 1985 and 2001. Annual inflation has fallen from 240% to less than 10 per cent. (Some have questioned whether Uganda’s economic growth rate can be sustained in the new millennium given the country’s involvement in the war in the Congo and the continuance of corruption in Uganda.) Under Museveni’s leadership, Uganda has instituted universal primary education and affirmative action policies that have empowered the nation’s women. He has also contributed to the country’s awareness of the AIDS problem and introduced grassroots health programs. Museveni takes credit for reducing absolute poverty from 56 per cent to 44 per cent, and increasing school enrollment from 2.5 million to 6.8 million. He proudly points out that there was one university in Uganda in 1986, but in 2001 there were 13.

But as his critics pointed out, Uganda is still not a traditional democracy where political parties operate unfettered. Museveni, however, has argued that political parties are inappropriate for Uganda in that they contribute to sectarian disputes, leading to racial antagonism and violence.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times in March 2000, Museveni elaborated, “[T]he constitution does not yet allow partisan political activities. This is due to the history of Africa, in general, but specifically the history of Uganda. The political parties in Europe and America evolved in tandem with the evolution of their societies. In Europe, a feudal, peasant society evolved into a middle-class, industrial one. Then social differentiation started emerging: the middle class, on the one side, and the industrial working class, on the other. They had contradictory interests. The middle class wanted to pay as little wages as possible to the workers, give them as little benefits as possible; the industrial workers wanted more and more pay and more benefits. To express their group interests in politics, they formed parties so that they could use the parties to bargain for group interests. The situation is still different in Africa. Societies are, in many ways, preindustrial. . . . There are many peasants. Their interests are homogenous. . . . When you form parties in that type of situation, on what would they be based? . . . Since there are no legitimate, antagonistic social interests to be represented, the danger is that these parties will become sectarian. We are trying to transplant the European experience onto the African reality, which is different.”

When asked whether he had designs on the Congo’s riches in natural resources, he replied, “First, we are not [even] able to exploit the riches of Uganda. . . . Those Congolese may not have heard that Uganda has one of the richest deposits of phosphates in Africa and even the world. We are not able to exploit it. It is just lying in the ground. We’ve got huge deposits of iron ore. We’ve got oil. Let’s first exploit them, before we go to the ones of Congo. We don’t have the capital to exploit our own resources. Why should we go for the ones of Congo?”

On the issue of U.S. reparations for slavery and colonialism, Museveni told the Los Angeles Times, “I don’t waste much time crying over spilt milk, because Africans are also to blame in a way. They were weak. They were not well-organized. African chiefs were the ones who were selling people into slavery, because of their shallowness. They were backward. They didn’t understand what was happening in the world. They didn’t understand their wider interests. . . . African weakness is what permitted the Europeans to exploit us, and [this] weakness must be solved. Now that we are back in control of our destinies, let us strengthen ourselves instead of remaining weak. Foolish people are always exploited. Let’s start afresh now. Even African Americans should build themselves . . . instead of just sitting there in the slums and saying the whites brought us here. . . . Of course, the whites should also be Christian, not take advantage.”

In 2000, Museveni identified the following three areas as most critical for Uganda in the following five years: “First, to ensure that we get more investment by removing all bottlenecks to investors. Second, to ensure that we continue to develop infrastructure, so that we lower our cost of production, so we can be able to sell, and that we continue to develop human resources through mass education. Finally, work for the East African market. An integrated market is a sine qua non of sustained growth of our economies. Part of our economic integration, we hope, should lead into a political union of East Africa . . . a political federation of at least East Africa.”

In March 2001, Ugandans returned to the polls to vote once again for their president. Museveni was the victor–this time with 69.% of the vote. As for how he would like to be remembered, Museveni told the Los Angeles Times: in 2000, “I will leave office, for sure, because I am not a hereditary king. I would be very glad to leave office, once I have served my term. To be remembered, just as a freedom fighter, who helped to give the people of Uganda a key to their future, to give them democracy, get rid of the dictatorship.”

Rishi Sunak, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (since Oct 25, 2022) Rishi Sunak (born…

Giorgia Meloni, Prime Minister of Italy (since Oct 22, 2022) Giorgia Meloni (born 15 January…

Mahamat Déby, President of Chad (since Oct 10, 2022) Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno (born 1…

João Lourenço, President of Angola (sworn in on Sept 26, 2017) Sworn in for his…

William Ruto, President of Kenya (elected on Aug 9, 2022 with 50.5% of the vote)…

Gustavo Petro, President of Colombia (since Aug 7, 2022) Gustavo Francisco Petro Urrego ODB ODSC…

This website uses cookies.

View Comments

A good analysis of the Museveni revolution.

Please give us up to date information beyond 2001. Otherwise that was comprehensively researched.